With most startups struggling to get funding in a cooled market, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) companies are in a completely different pool in 2023. According to Crunchbase, over half a billion dollars has gone to dozens of upstarts this past year. Crunchbase put together a list of companies with business models tied to carbon removal, capture, and storage that last secured funding in the past year. Noteworthy themes are:

- Marketplaces for carbon credits and measuring tools for enterprises, examples: Patch Technologies, Carbon Direct, Supercritical

- Decarbonization of industrial materials especially cement, or carbon-negative building materials, examples: Svante, Plantd, CarbonCure

- Carbon removal technologies, examples: Captura, Mombak

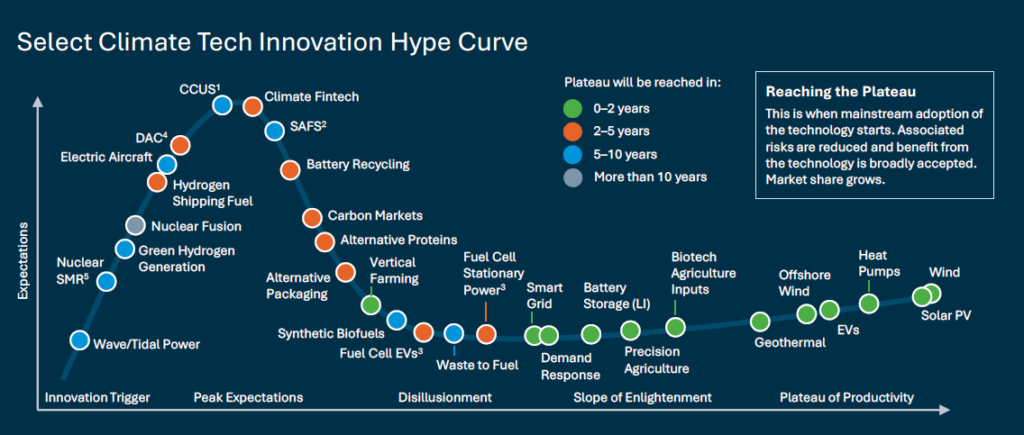

CCUS startup valuations have skyrocketed since the passing of the IRA. Silicon Valley Bank issued a nice report titled “The Future of Climate Tech” this June and placed CCUS at the peak of the hype cycle of climate tech.

This article likes to take a look at CCUS with a grain of salt. Numerous U.S. oil and gas producers have announced major CCUS projects in recent years. This includes the proposed $100 billion CCUS project in Houston under development by a group of companies led by ExxonMobil. This month (July, 2023) ExxonMobil just agreed to buy Denbury Inc for $4.9 billion (a small deal compared to its profit of $56B last year) to accelerate its energy transition business with an established carbon dioxide (CO2) sequestration operation, ExxonMobil has sought to build a carbon hub at Gulf Coast according to news, it can provide carbon reduction services quickly after this acquisition. The company already plans to store 2M tonnes of CO2 per year beginning in 2025 for Linde’s blue hydrogen and nitrogen facility in Beaumont, Texas, and has purchased a geologic permanent storage site in Louisiana.

Carbon sequestration has been embraced by oil companies including Chevron, Occidental Petroleum, and Talos Energy, which aim to capture and store CO2 underground. CCS is basically the only path for an O&G company to decarbonize while continuing its fossil fuels business. Drilling wells to store captured CO2 and managing the infrastructure to transport it allows Exxon to participate in the energy transition while leveraging existing expertise and assets.

This May (2023), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, proposed a new rule to nearly eliminate climate pollution from the nation’s coal- and natural gas-fired power plants by 2040. In contrast to previously proposed regulations that required “generation-shifting” — forcing utility companies to replace their fossil fuel-fired power generators with renewables, a strategy that the Supreme Court shut down last summer — the new proposal focuses on what’s achievable using technologies like carbon capture and storage, or CCS.

Wide-scale adoption of carbon sequestration remains uncertain because of the costs and technical challenges. The advertising/comms of O&G companies don’t really match their real impact, there is still a long way to go. CCS doesn’t have a strong track record of actually sequestering carbon — especially for the power sector, where 90 percent of the proposed carbon capture capacity has failed or never gotten off the ground (source). As reported by Time, some three dozen utility companies submitted a comment to the EPA last summer highlighting the “low likelihood” that CCS would be appropriate for use in the agency’s power plant regulations. They criticized the EPA for pointing to pilot projects as evidence of CCS’s viability. “A proposed or developing project … is not proof of a technology being available,” the utilities wrote.

A large volume of captured carbon is used for “enhanced oil recovery (EOR)” – a process where CO2 is pumped into oil fields in order to push more fossil fuels out of the ground. When burned, these fossil fuels release carbon back into the atmosphere, exacerbating global warming. This is just perpetuating the use and reliance on fossil fuels. For the carbon dioxide captured injected into dedicated underground storage reservoirs, it’s questionable whether it will stay put long-term. Ramping up carbon storage would develop a vast, expensive, and potentially dangerous network of CO2 pipelines. Also, CCS fails to address other pollutants like nitrogen oxides, which could continue to come out of power plants and harm nearby communities. A major blue hydrogen project in Louisiana is currently on hold due to local opposition over a plan to store any CO2 generated beneath a lake, as some residents fear it could pollute local water resources. McKinsey advocates that strategically building carbon capture, utilization, and storage hubs near clusters of large emitters can lower costs and accelerate scale-up.

Because of the huge push to decarbonize the industrial sector, which accounts for close to one-third of total U.S. emissions and is the most difficult to decarbonize. In March 2023, the IRA launched a $6 billion Industrial Demonstrations Program that funds up to 50% of the cost of each CCUS project. This represents a $12 billion opportunity for early-stage commercial-scale projects. The main problem with direct air capture is too energy-intensive, and therefore too expensive. That will still likely be the case in five, seven, or even 10 years, in a report by DCVC they were surprised to see hundreds of millions of dollars in capital flowing into early-stage direct air capture companies, such as Switzerland’s Climeworks, Canada’s Carbon Engineering, and U.S.-based Global Thermostat.

On the other hand, point source carbon capture is emerging and evolving faster, Carbon Clean builds modular chambers that use a liquid solvent to absorb flue gas at cement and steel plants and oil refineries; Remora, which can capture at least 80 percent of the CO₂ coming out the tailpipes of semitrucks; and Osmoses, which is developing novel gas-separation membranes that could lower the cost of carbon capture. Such technologies could become affordable in the foreseeable future. How to utilize the captured carbon safely with a viable cost structure is a topic worth another deep dive. (Promising Climate Tech – Carbon to Value)

“Pollution” by akeg is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Other references:

Comparing pathways to net-zero by BP, Shell, Chevron and ExxonMobil